First Intifada on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The First Intifada, or First Palestinian Intifada (also known simply as the intifada or intifadah),The word ''

5.

/ref> The intifada lasted from December 1987 until the

The accident that sparked an Intifada

12/04/2011 Palestinians charged that the collision was a deliberate response for the killing of a Jew in Gaza days earlier. Israel denied that the crash, which came at time of heightened tensions, was intentional or coordinated. The Palestinian response was characterized by protests, civil disobedience, and violence. There was

''How Fighting Ends: A History of Surrender,''

Oxford University Press 2012 pp. 417–433 p. 426.Wendy Pearlman, ''Violence, Nonviolence, and the Palestinian National Movement,''Cambridge University Press 2011

p. 114

Images of soldiers beating adolescents with clubs then led to the adoption of firing semi-lethal plastic bullets. In the intifada's first year, Israeli security forces killed 311 Palestinians, of which 53 were under the age of 17. Over six years the IDF killed an estimated 1,162–1,204Rami Nasrallah, 'The First and Second Palestinian Intifadas,' in Joel Peters, David Newman (eds.

''The Routledge Handbook on the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict''

Routledge 2013 pp. 56–68 p. 61 Palestinians. Among Israelis, 100 civilians and 60 IDF personnel were killedB'Tselem

Statistics; Fatalities in the first Intifada. often by militants outside the control of the Intifada's UNLU,Mient Jan Faber, Mary Kaldor, 'The deterioration of human security in Palestine,' in Mary Martin, Mary Kaldor (eds.

''The European Union and Human Security: External Interventions and Missions''

Routledge, 2009 pp. 95–111. and more than 1,400 Israeli civilians and 1,700 soldiers were injured. Intra-Palestinian violence was also a prominent feature of the Intifada, with widespread executions of an estimated 822 Palestinians killed as alleged Israeli collaborators (1988–April 1994). At the time Israel reportedly obtained information from some 18,000 Palestinians who had been compromised,Amitabh Pal

''"Islam" Means Peace: Understanding the Muslim Principle of Nonviolence Today''

ABC-CLIO, 2011 p. 191. although fewer than half had any proven contact with the Israeli authorities. Lockman; Beinin (1989), p.&nbs

/ref> The ensuing Second Intifada took place from September 2000 to 2005.

407.

/ref> After Israel's capture of the

401.

/ref> This was coupled with an expansion of a Palestinian university system catering to people from refugee camps, villages, and small towns generating new Palestinian elite from a lower social strata that was more activistic and confrontational with Israel. The

32.

/ref> During the 1980s a number of mainstream Israeli politicians referred to policies of transferring the Palestinian population out of the territories leading to Palestinian fears that Israel planned to evict them. Public statements calling for transfer of the Palestinian population were made by Deputy Defense minister

74.

/ref> Mass demonstrations had occurred a year earlier when, after two Gaza students at Birzeit University had been shot by Israeli soldiers on campus on 4 December 1986, the Israelis responded with harsh punitive measures, involving summary arrest, detention and systematic beatings of handcuffed Palestinian youths, ex-prisoners and activists, some 250 of whom were detained in four cells inside a converted army camp, known popularly as Ansar 11, outside Gaza city. A policy of deportation was introduced to intimidate activists in January 1987. Violence simmered as a schoolboy from

31.

/ref>

39.

/ref> The PLO's rivals in this activity were the Islamic organizations,

Israel's drive into the occupied territories had occasioned spontaneous acts of resistance, but the administration, pursuing an "iron fist" policy of deportations, demolition of homes, collective punishment, curfews and the suppression of political institutions, was confident that Palestinian resistance was exhausted. The assessment that the unrest would collapse proved to be mistaken.

Israel's drive into the occupied territories had occasioned spontaneous acts of resistance, but the administration, pursuing an "iron fist" policy of deportations, demolition of homes, collective punishment, curfews and the suppression of political institutions, was confident that Palestinian resistance was exhausted. The assessment that the unrest would collapse proved to be mistaken.

On 8 December 1987, an Israeli army tank transporter crashed into a row of cars containing Palestinians returning from working in Israel, at the Erez checkpoint. Four Palestinians, three of them residents of the

On 8 December 1987, an Israeli army tank transporter crashed into a row of cars containing Palestinians returning from working in Israel, at the Erez checkpoint. Four Palestinians, three of them residents of the

In the first year in the Gaza Strip alone, 142 Palestinians were killed, while no Israelis died. 77 were shot dead, and 37 died from tear-gas inhalation. 17 died from beatings at the hand of Israeli police or soldiers.

In the first year in the Gaza Strip alone, 142 Palestinians were killed, while no Israelis died. 77 were shot dead, and 37 died from tear-gas inhalation. 17 died from beatings at the hand of Israeli police or soldiers.

''Gaza: A History''

Oxford University Press p. 206. During the whole six-year intifada, the Israeli army killed from 1,162 to 1,204 (or 1,284)Juan José López-Ibor, Jr., George Christodoulou, Mario Maj, Norman Sartorius, Ahmed Okasha (eds.

''Disasters and Mental Health.''

John Wiley & Sons, 2005 p. 231. Palestinians, 241/332 being children. Between 57,000 and 120,000 were arrested, 481 were deported while 2,532 had their houses razed to the ground. Between December 1987 and June 1991, 120,000 were injured, 15,000 arrested and 1,882 homes demolished. One journalistic calculation reports that in the Gaza Strip alone from 1988 to 1993, some 60,706 Palestinians suffered injuries from shootings, beatings or tear gas.Nami Nasrallah, 'The First and Second Palestinian ''intifadas'',' in David Newman, Joel Peters (eds.

''Routledge Handbook on the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict,''

Routledge, 2013, pp. 56–67, p. 56. In the first five weeks alone, 35 Palestinians were killed and some 1,200 wounded. Some regarded the Israeli response as encouraging more Palestinians into participating.

2."> 2.

/ref> In an article in the London Review of Books,

115.

/ref>

/ref> Nassar; Heacock (1990), p.&nbs

1.

/ref> The Intifada broke the image of Jerusalem as a united Israeli city. There was unprecedented international coverage, and the Israeli response was criticized in media outlets and international fora.UNGA

''Resolution "43/21. The uprising (intifadah) of the Palestinian people"''

. 3 November 1988 (doc.nr. A/RES/43/21). Shlaim (2000), p. 455. The success of the Intifada gave Yasser Arafat, Arafat and his followers the confidence they needed to moderate their political programme: At the meeting of the Palestine National Council in Algiers in mid-November 1988, Arafat won a majority for the historic decision to recognise Israel's legitimacy; to accept all the relevant UN resolutions going back to 29 November 1947; and to adopt the principle of a

37.

/ref> The impact on the Israeli services sector, including the important Israeli tourist industry, was notably negative.Noga Collins-kreiner, Nurit Kliot, Yoel Mansfeld, Keren Sagi (2006) ''Christian Tourism to the Holy Land: Pilgrimage During Security Crisis'' Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., and

civilresistance.info

* * * * *

(www.intifada.com)

(Guardian, UK)

The Future of a Rebellion – Palestine

An analysis of the 1980s intifada revolt of Palestinian youth. on libcom.org

U.S. Involvement with Palestine's Rebellions

from th

Dean Peter Krogh Foreign Affairs Digital Archives

Israel's Post-Soviet Expansion

from th

Dean Peter Krogh Foreign Affairs Digital Archives

{{Authority control 1987 in the Israeli Civil Administration area 20th-century conflicts Civil disobedience Ethnic riots Intifadas Israeli–Palestinian conflict Protests in the Israeli Civil Administration area Rebellions in Asia Riots and civil disorder in Israel Criminal rock-throwing

intifada

An intifada ( ar, انتفاضة ') is a rebellion or uprising, or a resistance movement. It is a key concept in contemporary Arabic usage referring to a legitimate uprising against oppression.Ute Meinel ''Die Intifada im Ölscheichtum Bahrain: ...

'' () is an Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walter ...

word meaning "uprising

Rebellion, uprising, or insurrection is a refusal of obedience or order. It refers to the open resistance against the orders of an established authority.

A rebellion originates from a sentiment of indignation and disapproval of a situation and ...

". Its strict Arabic transliteration is '. was a sustained series of Palestinian

Palestinians ( ar, الفلسطينيون, ; he, פָלַסְטִינִים, ) or Palestinian people ( ar, الشعب الفلسطيني, label=none, ), also referred to as Palestinian Arabs ( ar, الفلسطينيين العرب, label=non ...

protests and violent riots in the West Bank, Gaza Strip, and within Israel. The protests were against the Israeli occupation

Israeli-occupied territories are the lands that were captured and occupied by Israel during the Six-Day War of 1967. While the term is currently applied to the Palestinian territories and the Golan Heights, it has also been used to refer to a ...

of the West Bank

The West Bank ( ar, الضفة الغربية, translit=aḍ-Ḍiffah al-Ġarbiyyah; he, הגדה המערבית, translit=HaGadah HaMaʽaravit, also referred to by some Israelis as ) is a landlocked territory near the coast of the Mediter ...

and Gaza that had begun twenty years prior, in 1967. Lockman; Beinin (1989), p.&nbs5.

/ref> The intifada lasted from December 1987 until the

Madrid Conference

The Madrid Conference of 1991 was a peace conference, held from 30 October to 1 November 1991 in Madrid, hosted by Spain and co-sponsored by the United States and the Soviet Union. It was an attempt by the international community to revive the ...

in 1991, though some date its conclusion to 1993, with the signing of the Oslo Accords.

The intifada began on 9 December 1987, in the Jabalia

Jabalia also Jabalya ( ar, جباليا) is a Palestinian city located north of Gaza City. It is under the jurisdiction of the North Gaza Governorate, in the Gaza Strip. According to the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, Jabalia had a pop ...

refugee camp after an Israeli Defense Forces' (IDF) truck collided with a civilian car, killing four Palestinian workers, three of whom were from the Jabalia refugee camp

Jabalia Camp ( ar, مخيّم جباليا) is a Palestinian refugee camp located north of Jabalia in the Gaza Strip.

History

The Jabalia refugee camp is in the North Gaza Governorate, Gaza Strip. According to the Palestinian Central Bureau of ...

.Michael Omer-MaThe accident that sparked an Intifada

12/04/2011 Palestinians charged that the collision was a deliberate response for the killing of a Jew in Gaza days earlier. Israel denied that the crash, which came at time of heightened tensions, was intentional or coordinated. The Palestinian response was characterized by protests, civil disobedience, and violence. There was

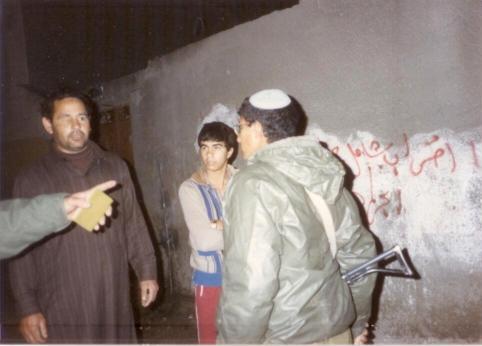

graffiti

Graffiti (plural; singular ''graffiti'' or ''graffito'', the latter rarely used except in archeology) is art that is written, painted or drawn on a wall or other surface, usually without permission and within public view. Graffiti ranges from s ...

, barricading, and widespread throwing of stones and Molotov cocktail

A Molotov cocktail (among several other names – ''see other names'') is a hand thrown incendiary weapon constructed from a frangible container filled with flammable substances equipped with a fuse (typically a glass bottle filled with fla ...

s at the IDF and its infrastructure within the West Bank and Gaza Strip. These contrasted with civil efforts including general strikes

A general strike refers to a strike action in which participants cease all economic activity, such as working, to strengthen the bargaining position of a trade union or achieve a common social or political goal. They are organised by large coa ...

, boycotts of Israeli Civil Administration

The Civil Administration ( he, המנהל האזרחי, '; ar, الإدارة المدنية الإسرائيلية) is the Israeli governing body that operates in the West Bank. It was established by the government of Israel in 1981, in order ...

institutions in the Gaza Strip

The Gaza Strip (;The New Oxford Dictionary of English (1998) – p.761 "Gaza Strip /'gɑːzə/ a strip of territory under the control of the Palestinian National Authority and Hamas, on the SE Mediterranean coast including the town of Gaza.. ...

and the West Bank

The West Bank ( ar, الضفة الغربية, translit=aḍ-Ḍiffah al-Ġarbiyyah; he, הגדה המערבית, translit=HaGadah HaMaʽaravit, also referred to by some Israelis as ) is a landlocked territory near the coast of the Mediter ...

, an economic boycott consisting of refusal to work in Israeli settlements on Israeli products, refusal to pay taxes, and refusal to drive Palestinian cars with Israeli licenses.

Israel deployed some 80,000 soldiers in response. Israeli countermeasures, which initially included the use of live rounds frequently in cases of riots, were criticized as disproportionate. The IDF's rules of engagement were also criticized as too liberally employing lethal force. Israel argued that violence from Palestinians necessitated a forceful response. In the first 13 months, 332 Palestinians and 12 Israelis were killed.Audrey Kurth Cronin 'Endless wars and no surrender,' in Holger Afflerbach, Hew Strachan (eds.''How Fighting Ends: A History of Surrender,''

Oxford University Press 2012 pp. 417–433 p. 426.Wendy Pearlman, ''Violence, Nonviolence, and the Palestinian National Movement,''Cambridge University Press 2011

p. 114

Images of soldiers beating adolescents with clubs then led to the adoption of firing semi-lethal plastic bullets. In the intifada's first year, Israeli security forces killed 311 Palestinians, of which 53 were under the age of 17. Over six years the IDF killed an estimated 1,162–1,204Rami Nasrallah, 'The First and Second Palestinian Intifadas,' in Joel Peters, David Newman (eds.

''The Routledge Handbook on the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict''

Routledge 2013 pp. 56–68 p. 61 Palestinians. Among Israelis, 100 civilians and 60 IDF personnel were killedB'Tselem

Statistics; Fatalities in the first Intifada. often by militants outside the control of the Intifada's UNLU,Mient Jan Faber, Mary Kaldor, 'The deterioration of human security in Palestine,' in Mary Martin, Mary Kaldor (eds.

''The European Union and Human Security: External Interventions and Missions''

Routledge, 2009 pp. 95–111. and more than 1,400 Israeli civilians and 1,700 soldiers were injured. Intra-Palestinian violence was also a prominent feature of the Intifada, with widespread executions of an estimated 822 Palestinians killed as alleged Israeli collaborators (1988–April 1994). At the time Israel reportedly obtained information from some 18,000 Palestinians who had been compromised,Amitabh Pal

''"Islam" Means Peace: Understanding the Muslim Principle of Nonviolence Today''

ABC-CLIO, 2011 p. 191. although fewer than half had any proven contact with the Israeli authorities. Lockman; Beinin (1989), p.&nbs

/ref> The ensuing Second Intifada took place from September 2000 to 2005.

General causes

According to Mubarak Awad, a Palestinian American clinical psychologist, the Intifada was a protest against Israeli repression including "beatings, shootings, killings, house demolitions, uprooting of trees, deportations, extended imprisonments, and detentions without trial". Ackerman; DuVall (2000), p&nbs407.

/ref> After Israel's capture of the

West Bank

The West Bank ( ar, الضفة الغربية, translit=aḍ-Ḍiffah al-Ġarbiyyah; he, הגדה המערבית, translit=HaGadah HaMaʽaravit, also referred to by some Israelis as ) is a landlocked territory near the coast of the Mediter ...

, Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

, Sinai Peninsula

The Sinai Peninsula, or simply Sinai (now usually ) (, , cop, Ⲥⲓⲛⲁ), is a peninsula in Egypt, and the only part of the country located in Asia. It is between the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Red Sea to the south, and is ...

and Gaza Strip

The Gaza Strip (;The New Oxford Dictionary of English (1998) – p.761 "Gaza Strip /'gɑːzə/ a strip of territory under the control of the Palestinian National Authority and Hamas, on the SE Mediterranean coast including the town of Gaza.. ...

from Jordan

Jordan ( ar, الأردن; tr. ' ), officially the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan,; tr. ' is a country in Western Asia. It is situated at the crossroads of Asia, Africa, and Europe, within the Levant region, on the East Bank of the Jordan Rive ...

and Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Medit ...

in the Six-Day War

The Six-Day War (, ; ar, النكسة, , or ) or June War, also known as the 1967 Arab–Israeli War or Third Arab–Israeli War, was fought between Israel and a coalition of Arab states (primarily Egypt, Syria, and Jordan) from 5 to 10 Ju ...

in 1967, frustration grew among Palestinians in the Israeli-occupied territories

Israeli-occupied territories are the lands that were captured and occupied by Israel during the Six-Day War of 1967. While the term is currently applied to the Palestinian territories and the Golan Heights, it has also been used to refer to a ...

. Israel opened its labor market to Palestinians in the newly occupied territories. Palestinians were recruited mainly to do unskilled or semi-skilled labor jobs Israelis did not want. By the time of the Intifada, over 40 percent of the Palestinian work force worked in Israel daily. Additionally, Israeli expropriation of Palestinian land, high birth rates in the West Bank and Gaza Strip and the limited allocation of land for new building and agriculture created conditions marked by growing population density and rising unemployment, even for those with university degrees. At the time of the Intifada, only one in eight college-educated Palestinians could find degree-related work. Ackerman; DuVall (2000), p&nbs401.

/ref> This was coupled with an expansion of a Palestinian university system catering to people from refugee camps, villages, and small towns generating new Palestinian elite from a lower social strata that was more activistic and confrontational with Israel. The

Israeli Labor Party

The Israeli Labor Party ( he, מִפְלֶגֶת הָעֲבוֹדָה הַיִּשְׂרְאֵלִית, ), commonly known as HaAvoda ( he, הָעֲבוֹדָה, , The Labor), is a social democratic and Zionist political party in Israel. The p ...

's Yitzhak Rabin

Yitzhak Rabin (; he, יִצְחָק רַבִּין, ; 1 March 1922 – 4 November 1995) was an Israeli politician, statesman and general. He was the fifth Prime Minister of Israel, serving two terms in office, 1974–77, and from 1992 until h ...

, then Defense Minister

A defence minister or minister of defence is a cabinet official position in charge of a ministry of defense, which regulates the armed forces in sovereign states. The role of a defence minister varies considerably from country to country; in s ...

, added deportations in August 1985 to Israel's "Iron Fist" policy of cracking down on Palestinian nationalism. This, which led to 50 deportations in the following 4 years, was accompanied by economic integration and increasing Israeli settlements such that the Jewish settler population in the West Bank alone nearly doubled from 35,000 in 1984 to 64,000 in 1988, reaching 130,000 by the mid nineties. Referring to the developments, Israeli minister of Economics and Finance, Gad Ya'acobi, stated that "a creeping process of ''de facto'' annexation" contributed to a growing militancy in Palestinian society. Lockman; Beinin (1989), p.&nbs32.

/ref> During the 1980s a number of mainstream Israeli politicians referred to policies of transferring the Palestinian population out of the territories leading to Palestinian fears that Israel planned to evict them. Public statements calling for transfer of the Palestinian population were made by Deputy Defense minister

Michael Dekel

Michael Dekel ( he, מיכאל דקל, 1 August 1920 – 20 September 1994) was an Israeli politician who served as a member of the Knesset for Likud between 1977 and 1988.

Biography

Dekel was born in Pińsk, Poland (now in Belarus). During Wor ...

, Cabinet Minister Mordechai Tzipori and government Minister Yosef Shapira

Yosef Shapira ( he, יוסף שפירא, 26 December 1926 – 28 December 2013) was an Israeli politician and educator who served as Minister without Portfolio between 1984 and 1988, although he was never a member of the Knesset.

Born in Jerusa ...

among others. Describing the causes of the Intifada, Benny Morris refers to the "all-pervading element of humiliation", caused by the protracted occupation which he says was "always a brutal and mortifying experience for the occupied" and was "founded on brute force, repression and fear, collaboration and treachery, beatings and torture chambers, and daily intimidation, humiliation, and manipulation"

Background

While the catalyst for the First Intifada is generally dated to a truck incident involving several Palestinian fatalities at the Erez Crossing in December 1987, Mazin Qumsiyeh argues, againstDonald Neff

Donald Lloyd Neff (October 15, 1930 – May 10, 2015) was an American author and journalist. Born in York, Pennsylvania, he spent 16 years in service for ''Time'', and was a former ''Time'' bureau chief in Israel. He also worked for ''The Washi ...

, that it began with multiple youth demonstrations earlier in the preceding month. Some sources consider that the perceived IDF failure in late November 1987 to stop a Palestinian guerrilla operation, the Night of the Gliders, in which six Israeli soldiers were killed, helped catalyze local Palestinians to rebel. Shay (2005), p.&nbs74.

/ref> Mass demonstrations had occurred a year earlier when, after two Gaza students at Birzeit University had been shot by Israeli soldiers on campus on 4 December 1986, the Israelis responded with harsh punitive measures, involving summary arrest, detention and systematic beatings of handcuffed Palestinian youths, ex-prisoners and activists, some 250 of whom were detained in four cells inside a converted army camp, known popularly as Ansar 11, outside Gaza city. A policy of deportation was introduced to intimidate activists in January 1987. Violence simmered as a schoolboy from

Khan Yunis

Khan Yunis ( ar, خان يونس, also spelled Khan Younis or Khan Yunus; translation: ''Caravansary fJonah'') is a city in the southern Gaza Strip. According to the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, Khan Yunis had a population of 142,6 ...

was shot dead by Israelis soldiers pursuing him in a Jeep. Over the summer the IDF's Lieutenant Ron Tal, who was responsible for guarding detainees at Ansar 11, was shot dead at point-blank range while stuck in a Gaza traffic jam. A curfew forbidding Gaza residents from leaving their homes was imposed for three days, during the Islamic holiday of Eid al-Adha

Eid al-Adha () is the second and the larger of the two main holidays celebrated in Islam (the other being Eid al-Fitr). It honours the willingness of Ibrahim (Abraham) to sacrifice his son Ismail (Ishmael) as an act of obedience to Allah's co ...

. In two incidents on 1 and 6 October 1987, respectively, the IDF

IDF or idf may refer to:

Defence forces

* Irish Defence Forces

* Israel Defense Forces

*Iceland Defense Force, of the US Armed Forces, 1951-2006

* Indian Defence Force, a part-time force, 1917

Organizations

* Israeli Diving Federation

* Interac ...

ambushed and killed seven Gaza men, reportedly affiliated with Islamic Jihad, who had escaped from prison in May. Some days later, a 17-year-old schoolgirl, Intisar al-'Attar, was shot in the back while in her schoolyard in Deir al-Balah

Deir al-Balah or Deir al Balah ( ar, دير البلح, , Monastery of the Date Palm) is a Palestinian city in the central Gaza Strip and the administrative capital of the Deir el-Balah Governorate. It is located over south of Gaza City. The c ...

by a settler in the Gaza Strip. The Arab summit in Amman

Amman (; ar, عَمَّان, ' ; Ammonite language, Ammonite: 𐤓𐤁𐤕 𐤏𐤌𐤍 ''Rabat ʻAmān'') is the capital and largest city of Jordan, and the country's economic, political, and cultural center. With a population of 4,061,150 a ...

in November 1987 focused on the Iran–Iraq War

The Iran–Iraq War was an armed conflict between Iran and Iraq that lasted from September 1980 to August 1988. It began with the Iraqi invasion of Iran and lasted for almost eight years, until the acceptance of United Nations Security Council ...

, and the Palestinian issue was shunted to the sidelines for the first time in years. Shalev (1991), p. 33. Nassar; Heacock (1990), p.&nbs31.

/ref>

Leadership and aims

The Intifada was not initiated by any single individual or organization. Local leadership came from groups and organizations affiliated with the PLO that operated within the Occupied Territories;Fatah

Fatah ( ar, فتح '), formerly the Palestinian National Liberation Movement, is a Palestinian nationalist social democratic political party and the largest faction of the confederated multi-party Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) and ...

, the Popular Front

A popular front is "any coalition of working-class and middle-class parties", including liberal and social democratic ones, "united for the defense of democratic forms" against "a presumed Fascist assault".

More generally, it is "a coalition ...

, the Democratic Front and the Palestine Communist Party

The Palestine Communist Party ( yi, פאלעסטינישע קומוניסטישע פארטיי, ''Palestinische Komunistische Partei'', abbreviated PKP; ar, الحزب الشيوعي الفلسطيني) was a political party in British Mandate ...

. Lockman; Beinin (1989), p.&nbs39.

/ref> The PLO's rivals in this activity were the Islamic organizations,

Hamas

Hamas (, ; , ; an acronym of , "Islamic Resistance Movement") is a Palestinian Sunni-Islamic fundamentalist, militant, and nationalist organization. It has a social service wing, Dawah, and a military wing, the Izz ad-Din al-Qassam Bri ...

and Islamic Jihad as well as local leadership in cities such as Beit Sahour

Beit Sahour or Beit Sahur ( ar, بيت ساحور pronounced ; Palestine grid 170/123) is a Palestinian town east of Bethlehem, in the Bethlehem Governorate of the State of Palestine. The city is under the administration of the Palestinian Nation ...

and Bethlehem

Bethlehem (; ar, بيت لحم ; he, בֵּית לֶחֶם '' '') is a city in the central West Bank, Palestine, about south of Jerusalem. Its population is approximately 25,000,Amara, 1999p. 18.Brynen, 2000p. 202. and it is the capital o ...

. However, the intifada was predominantly led by community councils led by Hanan Ashrawi

Hanan Daoud Mikhael Ashrawi ( ar, حنان داوود مخايل عشراوي ; born 8 October 1946) is a Palestinian politician, legislator, activist, and scholar who served as a member of the Leadership Committee and as an official spokesperson ...

, Faisal Husseini

Faisal Abdel Qader Al-Husseini ( ar, فيصل عبدالقادر الحسيني) (July 17, 1940 – May 31, 2001) was a Palestinian politician.

Al-Husseini was born in Baghdad, Kingdom of Iraq, son of Abd al-Qadir al-Husayni, commander of local ...

and Haidar Abdel-Shafi

Haidar Abdel-Shafi (Heidar Abdul-Shafi) ( ar, حيدر عبد الشافي June 10, 1919 – September 25, 2007), was a Palestinian physician, community leader and political leader who was the head of the Palestinian delegation to the Madrid C ...

, that promoted independent networks for education (underground schools as the regular schools were closed by the military in reprisal), medical care, and food aid. The Unified National Leadership of the Uprising

The Unified National Leadership of the Uprising (UNLU) (al-Qiyada al Muwhhada) is a coalition of the Local Palestinian leadership. During the First Intifada it played an important role in mobilizing grassroots support for the uprising. In 1987 The ...

(UNLU) gained credibility where the Palestinian society complied with the issued communiques. There was a collective commitment to abstain from lethal violence, a notable departure from past practice, which, according to Shalev arose from a calculation that recourse to arms would lead to an Israeli bloodbath and undermine the support they had in Israeli liberal quarters. The PLO and its chairman Yassir Arafat had also decided on an unarmed strategy, in the expectation that negotiations at that time would lead to an agreement with Israel. Pearlman attributes the non-violent character of the uprising to the movement's internal organization and its capillary outreach to neighborhood committees that ensured that lethal revenge would not be the response even in the face of Israeli state repression. Hamas and Islamic Jihad cooperated with the leadership at the outset, and throughout the first year of the uprising conducted no armed attacks, except for the stabbing of a soldier in October 1988, and the detonation of two roadside bombs, which had no impact.

Leaflets publicizing the intifada aims demanded the complete withdrawal of Israel from the territories it had occupied in 1967: the lifting of curfews and checkpoints; it appealed to Palestinians to join in civic resistance, while asking them not to employ arms, since military resistance would only invite devastating retaliation from Israel; it also called for the establishment of the Palestinian state on the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, abandoning the standard rhetorical calls, still current at the time, for the "liberation" of all of Palestine.

The Intifada

Israel's drive into the occupied territories had occasioned spontaneous acts of resistance, but the administration, pursuing an "iron fist" policy of deportations, demolition of homes, collective punishment, curfews and the suppression of political institutions, was confident that Palestinian resistance was exhausted. The assessment that the unrest would collapse proved to be mistaken.

Israel's drive into the occupied territories had occasioned spontaneous acts of resistance, but the administration, pursuing an "iron fist" policy of deportations, demolition of homes, collective punishment, curfews and the suppression of political institutions, was confident that Palestinian resistance was exhausted. The assessment that the unrest would collapse proved to be mistaken.

On 8 December 1987, an Israeli army tank transporter crashed into a row of cars containing Palestinians returning from working in Israel, at the Erez checkpoint. Four Palestinians, three of them residents of the

On 8 December 1987, an Israeli army tank transporter crashed into a row of cars containing Palestinians returning from working in Israel, at the Erez checkpoint. Four Palestinians, three of them residents of the Jabalya

Jabalia also Jabalya ( ar, جباليا) is a Palestinian city located north of Gaza City. It is under the jurisdiction of the North Gaza Governorate, in the Gaza Strip. According to the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, Jabalia had a po ...

refugee camp, the largest of the eight refugee camps in the Gaza Strip, were killed and seven others seriously injured. The traffic incident was witnessed by hundreds of Palestinian labourers returning home from work. The funerals, attended by 10,000 people from the camp that evening, quickly led to a large demonstration. Rumours swept the camp that the incident was an act of intentional retaliation for the stabbing to death of an Israeli businessman, killed while shopping in Gaza two days earlier. Following the throwing of a petrol bomb at a passing patrol car in the Gaza Strip on the following day, Israeli forces, firing with live ammunition and tear gas canisters into angry crowds, shot one young Palestinian dead and wounded 16 others.

On 9 December, several popular and professional Palestinian leaders held a press conference in West Jerusalem with the Israeli League for Human and Civil Rights in response to the deterioration of the situation. While they convened, reports came in that demonstrations at the Jabalya camp were underway and that a 17-year-old youth had been shot to death after throwing a petrol bomb at Israeli soldiers. She would later become known as the first martyr

A martyr (, ''mártys'', "witness", or , ''marturia'', stem , ''martyr-'') is someone who suffers persecution and death for advocating, renouncing, or refusing to renounce or advocate, a religious belief or other cause as demanded by an externa ...

of the intifada.'Intifada,' in David Seddon,(ed.) ''A Political and Economic Dictionary of the Middle East'', p. 284. Protests rapidly spread into the West Bank and East Jerusalem. Youths took control of neighbourhoods, closed off camps with barricades of garbage, stone and burning tires, meeting soldiers who endeavoured to break through with petrol bombs. Palestinian shopkeepers closed their businesses, and labourers refused to turn up to their work in Israel. Israel defined these activities as 'riots', and justified the repression as necessary to restore 'law and order'. Within days the occupied territories were engulfed in a wave of demonstrations and commercial strikes on an unprecedented scale. Specific elements of the occupation were targeted for attack: military vehicles, Israeli buses and Israeli banks. None of the dozen Israeli settlements were attacked and there were no Israeli fatalities from stone-throwing at cars at this early period of the outbreak. Equally unprecedented was the extent of mass participation in these disturbances: tens of thousands of civilians, including women and children. The Israeli security forces used the full panoply of crowd control measures to try and quell the disturbances: cudgels, nightsticks, tear gas

Tear gas, also known as a lachrymator agent or lachrymator (), sometimes colloquially known as "mace" after the early commercial aerosol, is a chemical weapon that stimulates the nerves of the lacrimal gland in the eye to produce tears. In ...

, water cannons, rubber bullets, and live ammunition. But the disturbances only gathered momentum. Shlaim (2000), pp. 450–1.

Soon there was widespread rock-throwing, road-blocking and tire burning throughout the territories. By 12 December, six Palestinians had died and 30 had been injured in the violence. The next day, rioters threw a gasoline bomb at the U.S. consulate in East Jerusalem

East Jerusalem (, ; , ) is the sector of Jerusalem that was held by Jordan during the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, as opposed to the western sector of the city, West Jerusalem, which was held by Israel.

Jerusalem was envisaged as a separat ...

though no one was hurt. The Israeli police and military response also led to a number of injuries and deaths. The IDF killed many Palestinians at the beginning of the Intifada, the majority killed during demonstrations and riots. Since initially a high proportion of those killed were civilians and youths, Yitzhak Rabin adopted a fallback policy of 'might, power and beatings'. Israel used mass arrest

A mass arrest occurs when police apprehend large numbers of suspects at once. This sometimes occurs at protests. Some mass arrests are also used in an effort to combat gang activity. This is sometimes controversial, and lawsuits sometimes result. I ...

s of Palestinians, engaged in collective punishments like closing down West Bank universities for most years of the intifada, and West Bank schools for a total of 12 months. Hebron University was closed by the army from January 1988 to June 1991. Round-the-clock curfews were imposed over 1600 times in just the first year. Communities were cut off from supplies of water, electricity and fuel. At any one time, 25,000 Palestinians would be confined to their homes. Trees were uprooted on Palestinians farms, and agricultural produce blocked from being sold. In the first year over 1,000 Palestinians had their homes either demolished or blocked up. Settlers also engaged in private attacks on Palestinians. Palestinian refusals to pay taxes were met with confiscations of property and licenses, new car taxes, and heavy fines for any family whose members had been identified as stone-throwers.

Casualties

In the first year in the Gaza Strip alone, 142 Palestinians were killed, while no Israelis died. 77 were shot dead, and 37 died from tear-gas inhalation. 17 died from beatings at the hand of Israeli police or soldiers.

In the first year in the Gaza Strip alone, 142 Palestinians were killed, while no Israelis died. 77 were shot dead, and 37 died from tear-gas inhalation. 17 died from beatings at the hand of Israeli police or soldiers.Jean-Pierre Filiu

Jean-Pierre Filiu (born in Paris, 1961) is a French professor of Middle East studies at Sciences Po, Paris School of International Affairs, an orientalist and an arabist.

Life and career

Before joining Sciences Po in 2006, Jean-Pierre Filiu ...

''Gaza: A History''

Oxford University Press p. 206. During the whole six-year intifada, the Israeli army killed from 1,162 to 1,204 (or 1,284)Juan José López-Ibor, Jr., George Christodoulou, Mario Maj, Norman Sartorius, Ahmed Okasha (eds.

''Disasters and Mental Health.''

John Wiley & Sons, 2005 p. 231. Palestinians, 241/332 being children. Between 57,000 and 120,000 were arrested, 481 were deported while 2,532 had their houses razed to the ground. Between December 1987 and June 1991, 120,000 were injured, 15,000 arrested and 1,882 homes demolished. One journalistic calculation reports that in the Gaza Strip alone from 1988 to 1993, some 60,706 Palestinians suffered injuries from shootings, beatings or tear gas.Nami Nasrallah, 'The First and Second Palestinian ''intifadas'',' in David Newman, Joel Peters (eds.

''Routledge Handbook on the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict,''

Routledge, 2013, pp. 56–67, p. 56. In the first five weeks alone, 35 Palestinians were killed and some 1,200 wounded. Some regarded the Israeli response as encouraging more Palestinians into participating.

B'Tselem

B'Tselem ( he, בצלם, , " in the image of od) is a Jerusalem-based non-profit organization whose stated goals are to document human rights violations in the Israeli-occupied Palestinian territories, combat any denial of the existence of su ...

calculated 179 Israelis killed, while official Israeli statistics place the total at 200 over the same period. 3,100 Israelis, 1,700 of them soldiers, and 1,400 civilians suffered injuries. By 1990 Ktzi'ot Prison

Ktzi'ot Prison (, ) is an Israeli detention facility located in the Negev desert south-west of Beersheba. It is Israel's largest detention facility in terms of land area, encompassing . It is also the largest detention camp in the world.

During ...

in the Negev

The Negev or Negeb (; he, הַנֶּגֶב, hanNegév; ar, ٱلنَّقَب, an-Naqab) is a desert and semidesert region of southern Israel. The region's largest city and administrative capital is Beersheba (pop. ), in the north. At its southe ...

held approximately one out of every 50 West Bank and Gazan males older than 16 years. Gerald Kaufman remarked: " iends of Israel as well as foes have been shocked and saddened by that country's response to the disturbances." McDowall (1989), p.&nbs2."> 2.

/ref> In an article in the London Review of Books,

John Mearsheimer

John Joseph Mearsheimer (; born December 14, 1947) is an American political scientist and international relations scholar, who belongs to the realist school of thought. He is the R. Wendell Harrison Distinguished Service Professor at the Univers ...

and Stephen Walt asserted that IDF soldiers were given truncheons and encouraged to break the bones of Palestinian protesters. The Swedish

Swedish or ' may refer to:

Anything from or related to Sweden, a country in Northern Europe. Or, specifically:

* Swedish language, a North Germanic language spoken primarily in Sweden and Finland

** Swedish alphabet, the official alphabet used by ...

branch of Save the Children

The Save the Children Fund, commonly known as Save the Children, is an international non-governmental organization established in the United Kingdom in 1919 to improve the lives of children through better education, health care, and economic ...

estimated that "23,600 to 29,900 children required medical treatment for their beating injuries in the first two years of the Intifada", one third of whom were children under the age of ten years.

Israel adopted a policy of arresting key representatives of Palestinian institutions. After lawyers in Gaza went on strike to protest their inability to visit their detained clients, Israel detained the deputy head of its association without trial for six months. Dr. Zakariya al-Agha, the head of the Gaza Medical Association, was likewise arrested and held for a similar period of detention, as were several women active in Women's Work Committees. During Ramadan, many camps in Gaza were placed under curfew for weeks, impeding residents from buying food, and Al-Shati

Al-Shati ( ar, مخيّم الشاطئ), also known as Beach camp, is a Palestinian refugee camp located in the northern Gaza Strip along the Mediterranean Sea coastline in the Gaza Governorate, and more specifically Gaza City. The camp's total ...

, Jabalya and Burayj were subjected to saturation bombing by tear gas. During the first year of the Intifada, the total number of casualties in the camps from such bombing totalled 16.

Intra-communal violence

Between 1988 and 1992, intra-Palestinian violence claimed the lives of nearly 1,000. By June 1990, according to Benny Morris, " e Intifada seemed to have lost direction. A symptom of the PLO's frustration was the great increase in the killing of suspected collaborators." Morris (1999), p. 612. Roughly 18,000 Palestinians, compromised by Israeli intelligence, are said to have given information to the other side. Collaborators were threatened with death or ostracism unless they desisted, and if their collaboration with the Occupying Power continued, were executed by special troops such as the "Black Panthers" and "Red Eagles". An estimated 771 (according toAssociated Press

The Associated Press (AP) is an American non-profit news agency headquartered in New York City. Founded in 1846, it operates as a cooperative, unincorporated association. It produces news reports that are distributed to its members, U.S. newspa ...

) to 942 (according to the IDF) Palestinians were executed on suspicion of collaboration during the span of the Intifada.

Other notable events

On 16 April 1988, a leader of the PLO, Khalil al-Wazir, ''nom de guerre'' Abu Jihad or 'Father of the Struggle', was assassinated inTunis

''Tounsi'' french: Tunisois

, population_note =

, population_urban =

, population_metro = 2658816

, population_density_km2 =

, timezone1 = CET

, utc_offset1 ...

by an Israeli commando squad. Israel claimed he was the 'remote-control "main organizer" of the revolt', and perhaps believed that his death would break the back of the intifada. During the mass demonstrations and mourning in Gaza that followed, two of the main mosques of Gaza were raided by the IDF and worshippers were beaten and tear-gassed. In total between 11 and 15 Palestinians were killed during the demonstrations and riots in Gaza and West Bank that followed al-Wazir's death. In June of that year, the Arab League

The Arab League ( ar, الجامعة العربية, ' ), formally the League of Arab States ( ar, جامعة الدول العربية, '), is a regional organization in the Arab world, which is located in Northern Africa, Western Africa, E ...

agreed to support the intifada financially at the 1988 Arab League summit. The Arab League reaffirmed its financial support in the 1989 summit.

Israeli defense minister Yitzhak Rabin

Yitzhak Rabin (; he, יִצְחָק רַבִּין, ; 1 March 1922 – 4 November 1995) was an Israeli politician, statesman and general. He was the fifth Prime Minister of Israel, serving two terms in office, 1974–77, and from 1992 until h ...

's response was: "We will teach them there is a price for refusing the laws of Israel." When time in prison did not stop the activists, Israel crushed the boycott by imposing heavy fines and seizing and disposing of equipment, furnishings, and goods from local stores, factories and homes. Aburish, Said K. (1998). ''Arafat: From Defender to Dictator''. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing

Bloomsbury Publishing plc is a British worldwide publishing house of fiction and non-fiction. It is a constituent of the FTSE SmallCap Index. Bloomsbury's head office is located in Bloomsbury, an area of the London Borough of Camden. It has a U ...

pp. 201-228

On 8 October 1990, 22 Palestinians were killed by Israeli police during the Temple Mount riots. This led the Palestinians to adopt more lethal tactics, with three Israeli civilians and one IDF soldier stabbed in Jerusalem and Gaza two weeks later. Incidents of stabbing persisted. The Israeli state apparatus carried out contradictory and conflicting policies that were seen to have injured Israel's own interests, such as the closing of educational establishments (putting more youths onto the streets) and issuing the Shin Bet

The Israel Security Agency (ISA; he, שֵׁירוּת הַבִּיטָּחוֹן הַכְּלָלִי; ''Sherut ha-Bitaẖon haKlali''; "the General Security Service"; ar, جهاز الأمن العام), better known by the acronym Shabak ( he, ...

list of collaborators. Nassar; Heacock (1990), p.&nbs115.

/ref>

Suicide bombing

A suicide attack is any violent attack, usually entailing the attacker detonating an explosive, where the attacker has accepted their own death as a direct result of the attacking method used. Suicide attacks have occurred throughout histor ...

s by Palestinian militants started on 16 April 1993 with the Mehola Junction bombing, carried at the end of the Intifada.

United Nations

The large number of Palestinian casualties provoked international condemnation. In subsequent resolutions, including 607 and 608, the Security Council demanded Israel cease deportations of Palestinians. In November 1988, Israel was condemned by a large majority of theUN General Assembly

The United Nations General Assembly (UNGA or GA; french: link=no, Assemblée générale, AG) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN), serving as the main deliberative, policymaking, and representative organ of the UN. Curr ...

for its actions against the intifada. The resolution was repeated in the following years.

Security Council

On 17 February 1989, theUN Security Council

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) is one of the Organs of the United Nations, six principal organs of the United Nations (UN) and is charged with ensuring international security, international peace and security, recommending the admi ...

drafted a resolution condemning Israel for disregarding Security Council resolutions, as well as for not complying with the fourth Geneva Convention. The United States, put a veto on a draft resolution which would have strongly deplored it. On 9 June, the US again put a veto on a resolution. On 7 November, the US vetoed a third draft resolution, condemning alleged Israeli violations of human rights

On 14 October 1990, Israel openly declared that it would not abide Security Council Resolution 672 because it did not pay attention to attacks on Jewish worshippers at the Western Wall

The Western Wall ( he, הַכּוֹתֶל הַמַּעֲרָבִי, HaKotel HaMa'aravi, the western wall, often shortened to the Kotel or Kosel), known in the West as the Wailing Wall, and in Islam as the Buraq Wall (Arabic: حَائِط � ...

. Israel refused to receive a delegation of the Secretary-General, which would investigate Israeli violence. The following Resolution 673 made little impression and Israel kept on obstructing UN investigations.

Outcomes

The Intifada was recognized as an occasion where the Palestinians acted cohesively and independently of their leadership or assistance of neighbouring Arab states. McDowall (1989), p.&nbs/ref> Nassar; Heacock (1990), p.&nbs

1.

/ref> The Intifada broke the image of Jerusalem as a united Israeli city. There was unprecedented international coverage, and the Israeli response was criticized in media outlets and international fora.UNGA

''Resolution "43/21. The uprising (intifadah) of the Palestinian people"''

. 3 November 1988 (doc.nr. A/RES/43/21). Shlaim (2000), p. 455. The success of the Intifada gave Yasser Arafat, Arafat and his followers the confidence they needed to moderate their political programme: At the meeting of the Palestine National Council in Algiers in mid-November 1988, Arafat won a majority for the historic decision to recognise Israel's legitimacy; to accept all the relevant UN resolutions going back to 29 November 1947; and to adopt the principle of a

two-state solution

The two-state solution to the Israeli–Palestinian conflict envisions an independent State of Palestine alongside the State of Israel, west of the Jordan River. The boundary between the two states is still subject to dispute and negotia ...

. Shlaim (2000), p. 466.

Jordan severed its residual administrative and financial ties to the West Bank in the face of sweeping popular support for the PLO. The failure of the "Iron Fist" policy, Israel's deteriorating international image, Jordan cutting legal and administrative ties to the West Bank, and the U.S.'s recognition of the PLO as the representative of the Palestinian people forced Rabin to seek an end to the violence though negotiation and dialogue with the PLO. Shlaim (2000), pp. 455–7.

In the diplomatic sphere, the PLO opposed the Persian Gulf War

The Gulf War was a 1990–1991 armed campaign waged by a 35-country military coalition in response to the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait. Spearheaded by the United States, the coalition's efforts against Iraq were carried out in two key phases: ...

in Iraq. Afterwards, the PLO was isolated diplomatically, with Kuwait and Saudi Arabia cutting off financial support, and 300,000-400,000 Palestinians fled or were expelled from Kuwait before and after the war. The diplomatic process led to the Madrid Conference

The Madrid Conference of 1991 was a peace conference, held from 30 October to 1 November 1991 in Madrid, hosted by Spain and co-sponsored by the United States and the Soviet Union. It was an attempt by the international community to revive the ...

and the Oslo Accords. Roberts; Garton Ash (2009) p.&nbs37.

/ref> The impact on the Israeli services sector, including the important Israeli tourist industry, was notably negative.Noga Collins-kreiner, Nurit Kliot, Yoel Mansfeld, Keren Sagi (2006) ''Christian Tourism to the Holy Land: Pilgrimage During Security Crisis'' Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., and

Timeline

See also

*1990 Temple Mount riots

The 1990 Temple Mount riots, or the Al Aqsa Massacre, also known as Black Monday, took place at the Temple Mount, Jerusalem at 10:30 am on Monday, 8 October 1990 before Zuhr prayer during the third year of the First Intifada. Following a decisio ...

* Second Intifada (2000–2005)

* 2014 Jerusalem unrest (2014)

* Israeli–Palestinian conflict (2015)

The Israeli–Palestinian conflict is one of the world's most enduring conflicts, beginning in the mid-20th century. Various attempts have been made to resolve the conflict as part of the Israeli–Palestinian peace process, alongside other eff ...

* Sumud (steadfastness)

* Palestinian nationalism

Palestinian nationalism is the national movement of the Palestinian people that espouses self-determination and sovereignty over the region of Palestine.de Waart, 1994p. 223 Referencing Article 9 of ''The Palestinian National Charter of 1968' ...

* Palestinian political violence

Palestinian political violence refers to acts of violence perpetrated for political ends in relation to the State of Palestine or in connection with Palestinian nationalism. Common political objectives include self-determination in and soverei ...

* List of modern conflicts in the Middle East

This is a list of modern conflicts in the Middle East ensuing in the geographic and political region known as the Middle East. The "Middle East" is traditionally defined as the Fertile Crescent (Mesopotamia), Levant, and Egypt and neighboring ...

Notes

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * , out-of-print, now downloadable acivilresistance.info

* * * * *

External links

(www.intifada.com)

(Guardian, UK)

The Future of a Rebellion – Palestine

An analysis of the 1980s intifada revolt of Palestinian youth. on libcom.org

U.S. Involvement with Palestine's Rebellions

from th

Dean Peter Krogh Foreign Affairs Digital Archives

Israel's Post-Soviet Expansion

from th

Dean Peter Krogh Foreign Affairs Digital Archives

{{Authority control 1987 in the Israeli Civil Administration area 20th-century conflicts Civil disobedience Ethnic riots Intifadas Israeli–Palestinian conflict Protests in the Israeli Civil Administration area Rebellions in Asia Riots and civil disorder in Israel Criminal rock-throwing